Magazine Ad for SOFTIMAGE 3D, SOFTIMAGE 3D Extreme, SOFTIMAGE Eddie, SOFTIMAGE Toonz, and SOFTIMAGE Painterly Effects

Category Archives: Friday Flashback

Friday Flashback #460

Friday Flashback #459

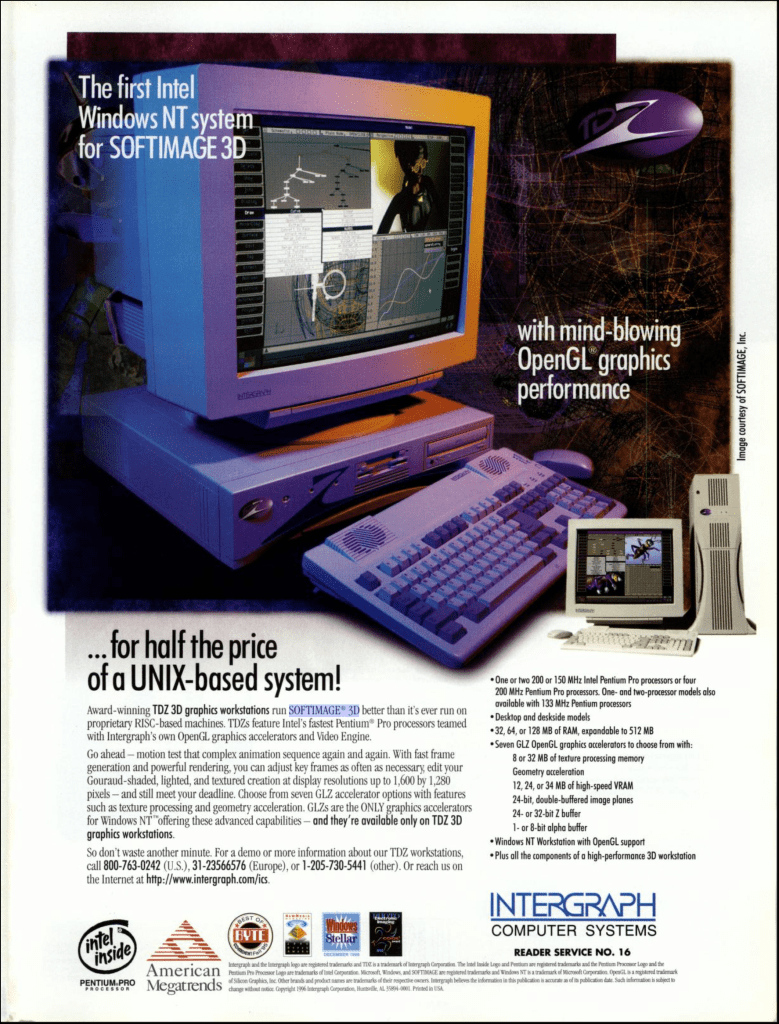

SOFTIMAGE NT

Friday Flashback #458

Friday Flashback #457

Friday Flashback #456

Inside the front cover of Inside SOFTIMAGE 3D

Friday Flashback #455

A making of (in German), then starting at about 4:30, some European productions…

Friday Flashback #454

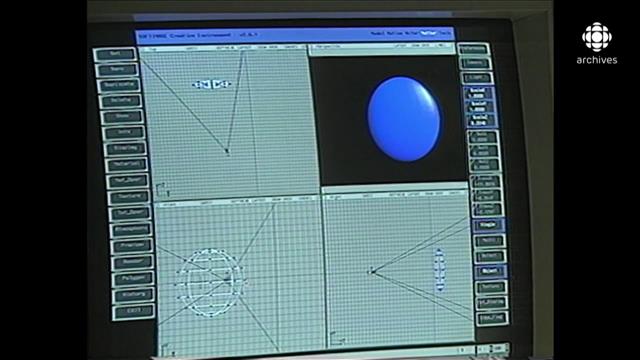

From the November 1992 issue of TV Technology, a review of the SoftImage Creative Environment.

When it came time to invest in a 3-D animation system, I selected the SoftImage Creative Environment on the Unix platform.

SoftImage renders the models through points, splines (lines connected by points), faces, polygons, and patches (3D surfaces).

Unlike usual cold-looking computer images, SoftImage-rendered images are closer to more traditional animation. This is achieved through selective ray tracing, which also saves rendering time by elminating the ray tracing of unwanted images.

Friday Flashback #453

From Radio Canada

Quand Le Parc jurassique a mis Montréal et Softimage sur la carte

Animation d’un dinosaure à l’aide du logiciel Softimage pour le film Le Parc jurassique en 1993

En juin 1993, la sortie du film Le Parc jurassique donne une renommée internationale à une entreprise montréalaise. C’est au logiciel Softimage qu’on doit les effets spéciaux renversants de la mégaproduction hollywoodienne. Retrouvez dans nos archives le parcours du fondateur de Softimage, Daniel Langlois.

Avant Le Parc jurassique, il y a eu Tony de Peltrie, le premier acteur synthétique du monde. Ce personnage est au cœur d’un film d’animation conçu au Centre de calcul de l’Université de Montréal.

Daniel Langlois fait partie de l’équipe de pionniers qui réalise cette innovation.

Le Point, 28 août 1985

À l’émission Le Point du 28 août 1985, l’animateur Simon Durivage s’entretient avec deux des créateurs de Tony de Peltrie, Daniel Langlois et Philippe Bergeron.

Le jeune artiste Daniel Langlois explique comment le personnage a été conçu entièrement par ordinateur. La grande innovation, selon lui, est d’avoir réussi à donner du « feeling » à cet humain virtuel. La technique d’animation développée par l’équipe accorde une haute importance aux expressions faciales afin de susciter des émotions.

Le film d’animation « a épaté les gens de Hollywood ». Flattés par cet intérêt, les créateurs de Tony de Peltrie expriment néanmoins leur préférence pour demeurer à Montréal et en faire un centre de créativité dans le domaine de l’animation.

C’est sur cet élan que Daniel Langlois fondera Softimage.

Découverte, 21 novembre 1993

Le Parc jurassique sera le grand succès cinématographique de l’été 1993. Les effets spéciaux du film ont été créés avec des outils informatiques de Softimage.

Ces dinosaures ne sont pas des maquettes robotisées, ils ont été conçus et animés par ordinateur. L’animateur de Découverte, Charles Tisseyre

L’émission Découverte du 21 novembre 1993 s’attarde à la technologie d’animation 3D utilisée dans le film. Le journaliste Claude D’Astous visite les bureaux de Softimage et s’entretient avec son président, Daniel Langlois.

De son propre aveu, Le Parc Jurassique marque un tournant dans l’histoire des effets spéciaux. Les dinosaures deviennent vraiment des acteurs et « c’est ce qu’on voulait atteindre », affirme Daniel Langlois. Un mot clé revient à plusieurs reprises au cours de l’entrevue : intégration.

Dressant l’historique de Softimage, le narrateur Charles Tisseyre décrit Daniel Langlois comme « un designer de profession et informaticien par nécessité ». Son logiciel, il l’a conçu afin de rendre l’animation 3D accessible aux dessinateurs et créateurs, des gens généralement peu attirés par l’informatique.

Avec Softimage Creative Environment, il est désormais possible de laisser cours à la création avec des outils informatiques conviviaux.

Téléjournal, 15 février 1994

Au Téléjournal du 15 février 1994, le chef d’antenne Bernard Derome annonce l’acquisition de l’une des « belles réussites montréalaises » par le géant américain Microsoft.

Le journaliste Réal D’amours donne des détails sur la transaction. Au moment de fonder son entreprise, Daniel Langlois avait eu du mal à obtenir un prêt de 500 000 $. Moins de 10 ans plus tard, il récolte 130 millions de dollars pour Softimage.

Daniel Langlois souhaite continuer à influencer l’industrie de l’animation. L’entente avec Microsoft prévoit que le budget accordé à la recherche et au développement sera triplé. L’entreprise demeurera également à Montréal.

Et 25 ans après Le Parc jurassique, Daniel Langlois a réussi son pari de faire de la métropole québécoise un centre de créativité.

Montréal est aujourd’hui considérée comme une plaque tournante de l’industrie des effets visuels. Elle se situe au troisième rang mondial dans ce secteur, aux côtés de Londres et de Vancouver.

Friday Flashback #452

From the Jan 2001 issue of Computer Graphics

Men in motion

by Karen Moltenbrey

To achieve more realistic animation in games, developers have been using standard motion-capture techniques to create unique, compelling character movements. Links DigiWorks of Tokyo, however, has taken motion capture in games much further-six times, in fact-while creating an opening cinematic sequence involving six characters for Capcom’s upcoming Onimusha: Warlords game, expected to be released this month, for the PlayStation 2 console.

Using a Vicon 8 system from Oxford Metrics, Links DigiWorks simultaneously captured the motions of six actors for integration into samurai battle sequences that appear in the cinematic. “With the Vicon 8, which was introduced last year, we are no longer limited to capturing the motion of just one person at a time,” says Koji Ichihashi, president of Links DigiWorks. “Previously, when we needed two or three people in a battle scene, we’d have to capture the motion of each one separately, and then try to match them up in a scene. By shooting all the movement at one time, the actions and reactions of the actors during a fight scenario remain natural, fluid, and realistic.”

Onimusha’s opening cinematic sets the stage for the game’s story line, depicting agile warriors battling to the death on behalf of their powerful, fearsome warlords during 1560 feudal Japan. The video console game, which is loosely based on historical events, blends fiction with fantasy through extraordinary 3D images that take advantage of the Play Station 2’s highly touted graphics capabilities.

Capcom wanted the game’s opening sequence to be of similar quality, so Links DigiWorks hired Japanese dramatic feature-film director Shimako Sato to help stage the drama. Using a Vicon 8 system, the Links DigiWorks team shot several takes of six actors, specially trained in samurai movements, performing various fighting actions during a four-day motion-capture session. To capture all the motion at once, the group used 12 cameras set up around a 20-meter square area that contained rigs, props, and wooden hills to help depict the terrain where the action occurs in the cinematic sequence. The movements of the props, including spears and other weapons, were also captured during the session.

The most challenging part of the project, according to Ichihashi, was sorting and analyzing the motion data from the 100-plus reflective markers placed on the actors and props. “We had to determine which markers belonged to which characters in the scene, which was an extremely complex process, because the actors were moving around so quickly and hidden by each other’s bodies.” Once the data was sorted, the group mapped it onto low-resolution Softimage character models for review and additional cleanup of the motion.

Although using motion capture proved arduous-it took nearly eight months to complete just the opening movie-Ichihashi still believes it was the best option. “We chose motion capture over keyframing because we wanted natural, performance-style animation, not Disney-style animation,” he says. Also, Ichihashi believes that motion capture will enable the studio to create animation data, particularly for feature films, more quickly and less expensively than they can with keyframing. This project, he estimates, likely would have taken two to three times longer using keyframing.

Creating lifelike motion, however, was only half the battle. To achieve the desired realism for the cinematic, the group needed photo-quality characters on which to map the movements. Using Softimage 3D running on a variety of hardware, they created the main character models, dressed in period clothing and textured with Adobe Systems’ Photoshop.

With the company’s customized software, the artists also incorporated hordes of warriors and riders on horseback into the animations, as well as special effects such as fog, smoke, and raindrops. “The crowds were especially difficult to control,” notes Ichihashi. “At times there were hundreds of people doing battle in the fields.” To complete the scenes, the group added backgrounds and non-character models, as well as special effects such as fire and fog using its particle software.

Rendering the sequence, which contains 40 to 50 layers, was done in Softimage, Discreet’s 3D Studio Max, and Links DigiWorks’ proprietary rendering software, which was used mostly for the effects. According to Ichihashi, the majority of the layers were rendered overnight using a variety of hardware, including SGI machines (O2s, Indys, and Indigo2s), Unix boxes, and NT workstations. Some layers, though, took days to render.