Getting the Renderer options for the current pass is just a one-liner:

Application.GetValue( "Passes.Current.RendererOptions" )

Getting the Renderer options for the current pass is just a one-liner:

Application.GetValue( "Passes.Current.RendererOptions" )

Let’s take a look at a question that was posted recently on the Softimage mailing list:

From: softimage-bounces@listproc.autodesk.com [mailto:softimage-bounces@listproc.autodesk.com] On Behalf Of Adam Sale

Sent: Tuesday, January 08, 2013 3:40 PM

To: softimage@listproc.autodesk.com

Subject: Force ppg to open on script launchI’m a little confused as to why the following does not work:

– Get a sphere

– Run Deform > Smooth

– PPG appears and all is good.Now, take the generated command and run it through the script editor

ApplyOp(“Smooth”, “torus”, 3, siPersistentOperation, null, 0);

This time, no PPG appears.

Any idea why? And is there a way to force a ppg launch when I tun the command from a button or from the script editor?

Thanks 🙂

Adam

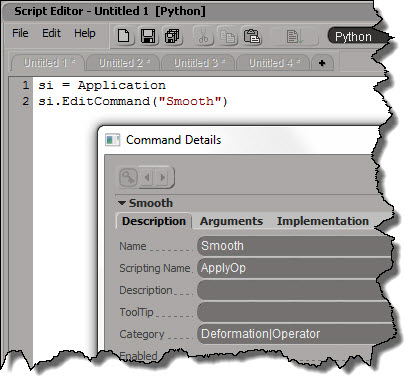

Matt Lind explained why on the list, but I’ll take a little more detailed look into how commands like Smooth work.

Deforms like Smooth (and Relax and Push and Bend and others) are commands that are mapped to a special handler function in $XSI_HOME\Application\DSScripts\operators.vbs.

The ApplyOpProc provides special-case handling for applying operators, and also takes care of popping up a PPG after the operator is applied.

Don’t try to run “Smooth”; you’ll just get an error. It’s scripting name is actually ApplyOp.

ApplyOp is also implemented by a VBScript handler in operator.vbs. This time, it’s ApplyOpFunc, and ApplyOpFunc does not inspect the created operators.

If you want to apply a Smooth operator from your script, and pop up the PPG after, here’s one way to do it:

si = Application

si.AutoInspect( si.ApplyOp("Smooth", si.Selection, 3, "siPersistentOperation", "", 0) )

Here’s a snippet that shows how to launch a command-line program in a command prompt window, and keep the command prompt window open so you can see the output. Note that does not block Softimage.

#sKick = "C:/Users/SOLIDANGLE/Documents/Workgroups/sitoa-2.5.0-2013/Addons/SItoA/Application/bin/nt-x86-64/kick.exe"

sKick = XSIUtils.BuildPath( Application.InstallationPath( 2 ), "Addons", "SItoA", "Application", "bin", XSIUtils.Environment("XSI_CPU_OPT"), "kick.exe" )

XSIUtils.LaunchProcess( "cmd /C start cmd /K %s -licensecheck" % sKick )

Basically, what this does is launch a cmd.exe process, and in that process, run the command “start cmd /K kick -licensecheck”. The second “cmd” is required to open a command prompt, where you’ll see the output of “kick -licensecheck”.

In JScript, it would be something similar:

sKick = XSIUtils.BuildPath( Application.InstallationPath( 2 ), "Addons", "SItoA", "Application", "bin", XSIUtils.Environment("XSI_CPU_OPT"), "kick.exe" )

XSIUtils.LaunchProcess( "cmd /C start cmd /K " + sKick + " -licensecheck" )

In Python, you could also do this:

from subprocess import call call(["cmd", "/K", sKick, "-licensecheck"])

The above would open a non-blocking command prompt window (eg you could go back to Softimage), but this next snippet would prevent Softmage from responding until you closed the command prompt:

import os

os.system("cmd /k %s -licensecheck" % sKick)

Early this week, I posted a script that did a random shuffle of a collection of objects. That script used tuple assignment to swap elements in a list; here’s a simpler example, with the tuple assignment (line 9) highlighted:

import random v = [o for o in Application.Selection] print [o.Name for o in v] # random shuffle for i in range( len(v) ): j = random.randint( i, len(v)-1 ) v[i], v[j] = v[j], v[i] print [o.Name for o in v] # [u'cube', u'cube1', u'cube2', u'cube3', u'cube4', u'cube5', u'cube6', u'cube7', u'cube8'] # [u'cube5', u'cube4', u'cube7', u'cube2', u'cube1', u'cube3', u'cube', u'cube8', u'cube6']

Looking at that line, you might wonder why you don’t end up assigning the same value to both a[i] and a[j] (eg, how does that line not do a[i] = a[j] and then a[j] = a[i] ?).

In tuple assignment, the right-hand side is considered a tuple of values. So the right-hand side is evaluated first, and then the resulting values are pairwise assigned to the tuple on the left hand side. For example, consider this-rather-more-concrete snippet:

a = 2 b = 8 a,b = b-a,b+a print a print b # 6 # 10

The right-hand side “b-a,b+a” is first evaluated, giving the tuple 6, 10, so you effectively have this:

a,b = 6,10

Via a tech-artists.org tweet, I came across some MAXScript for randomly selecting a specified percentage of mesh elements (for example, give me a random selection that includes 35% of all vertices).

Via a tech-artists.org tweet, I came across some MAXScript for randomly selecting a specified percentage of mesh elements (for example, give me a random selection that includes 35% of all vertices).

I converted it to Python in Softimage. Note that I don’t really shuffle a collection: you can’t set items in a collection, so there’s no way to swap items. Instead, I put the collection in a list and shuffle the list.

Shuffling actually makes this harder than it has to be. Check out Alan’s nice script for a better way to do this.

si = Application

log = si.LogMessage

sisel = si.Selection

#http://creativescratchpad.blogspot.ca/2011/06/select-random-elements-by-percentage.html

import random

#

# Return a list that includes a randomly selected

# percentage of the items in a collection

#

def get_random_percentage( collection, percentage ):

v = [x for x in collection]

# random shuffle

for i in range( len(v) ):

j = random.randint( i, len(v)-1 )

v[i], v[j] = v[j], v[i]

# select by percentage

step = 100/percentage

w = []

for i in xrange( 0, len(v), step ):

w.append( v[i] )

# print len(w)

# print (percentage/100.0) * len(v)

return w

Application.SelectObj("torus", "", True)

# Select a random 50% of the vertices

x = get_random_percentage( sisel(0).ActivePrimitive.Geometry.Vertices, 50 )

si.SelectObj(x)

print sisel(0).SubComponent.ComponentCollection.Count

# Suppose you had 2000 cubes.

# Select a random 25% of those 2000...

Application.SelectObj("cube*", "", True)

x = get_random_percentage( sisel, 25 )

si.SelectObj(x)

I learned a couple of things about MAXScript:

When you stick something, like say a Vertex, into an XSICollection, you get a CollectionItem. But you can get back to the Vertex if you know how (via the SubComponent

).

si = Application log = si.LogMessage sisel = si.Selection import win32com.client oColl = win32com.client.Dispatch( "XSI.Collection" ) o = sisel(0) print si.ClassName( o.ActivePrimitive.Geometry.Vertices(0) ) # Vertex #oColl.Add( o.ActivePrimitive.Geometry.Vertices(0) ) oColl.AddItems( o.ActivePrimitive.Geometry.Vertices ) print si.ClassName( oColl(0) ) # CollectionItem print si.ClassName( oColl(0).SubComponent.ComponentCollection(0) ) # Vertex a = o.ActivePrimitive.Geometry.Vertices(0) b = oColl(0).SubComponent.ComponentCollection(0) print a.IsEqualTo(b) # True print b.IsEqualTo(a) # True

Here’s something I was trying to do in ICE (without using any Repeats).

Given an array like

a = [ 5, 2 ,3 ]

create an array like

b = [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2 ]

See the pattern? (a[0] is 5, so array b has five elements with value 0).

In Python, using list comprehension, you can do it like this:

a = [ 5, 2, 3 ] print [ i for i in range( len(a) ) for j in range( a[i] )]

The list comprehension is the equivalent of:

for i in range( len(a) ): for j in range( a[i] ): print i

Here’s a script that goes through the SimulationEnvironments of a scene and find the 3d objects in each SimulationEnvironment. This snippet builds a dictionary of 3d objects, indexed by simulation environment.

from siutils import si

si = si() # win32com.client.Dispatch('XSI.Application')

from siutils import log # LogMessage

from siutils import disp # win32com.client.Dispatch

from siutils import C # win32com.client.constants

from xml.etree import ElementTree as ET

# Use a dictionary to store the 3d objects keyed by Environmen

dict = {}

for e in si.ActiveProject2.ActiveScene.SimulationEnvironments:

stack = XSIUtils.DataRepository.GetConnectionStackInfo( e.SimulationTimeControl )

xmlRoot = ET.fromstring( stack )

for xmlConnections in xmlRoot.findall('connection'):

o = xmlConnections.find( 'object' )

dict[ si.Dictionary.GetObject( o.text ).Parent3DObject.FullName ] = e.FullName

log( "3DObjects and their SimulationEnvironments" )

for key, value in dict.items():

log( "\t%s, %s" % (key,value) )

log( "" )

log( "SimulationEnvironments and 3DObjects" )

dictvals = set( dict.values() )

for env in dictvals:

log( "\t%s" % env )

list = [k for k, v in dict.iteritems() if v == env]

for o in list:

log( "\t\t%s" % o )

Here’s some sample output from the script:

# INFO : 3DObjects and their SimulationEnvironments # INFO : pointcloud1, Environments.Environment # INFO : Point_cloud_chaser.pointcloud2, Environments.Environment1 # INFO : grid, Environments.Environment # INFO : Point_cloud_chaser.pointcloud1, Environments.Environment1 # INFO : pointcloud, Environments.Environment # INFO : Point_cloud_chaser.pointcloud, Environments.Environment1 # INFO : # INFO : SimulationEnvironments and 3DObjects # INFO : Environments.Environment1 # INFO : Point_cloud_chaser.pointcloud2 # INFO : Point_cloud_chaser.pointcloud1 # INFO : Point_cloud_chaser.pointcloud # INFO : Environments.Environment # INFO : pointcloud1 # INFO : grid # INFO : pointcloud

Use IsEqualTo, don’t use your scriping language equality comparison operaor. For example, here I’m using IsEqualTo to check if an object’s material is the Scene_Material.

si = Application print si.Selection(0).Material.IsEqualTo( si.ActiveProject.ActiveScene.Root.Material )

Sometimes when you’re troubleshooting, it’s a good idea to check the environment in which Softimage is running.

You can check specific environment variables in the script editor like this:

import os print os.getenv( "XSI_USERHOME" ) print os.getenv( "TEMP" )

or like this:

print XSIUtils.Environment("XSI_BINDIR")

But I would typically use Process Explorer to see the full environment:

or Process Monitor (in Process Monitor, you just have to find the Process Start operation for XSI.exe and double-click it).